25 years later, the trauma of the Columbine High School shooting is still with us

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

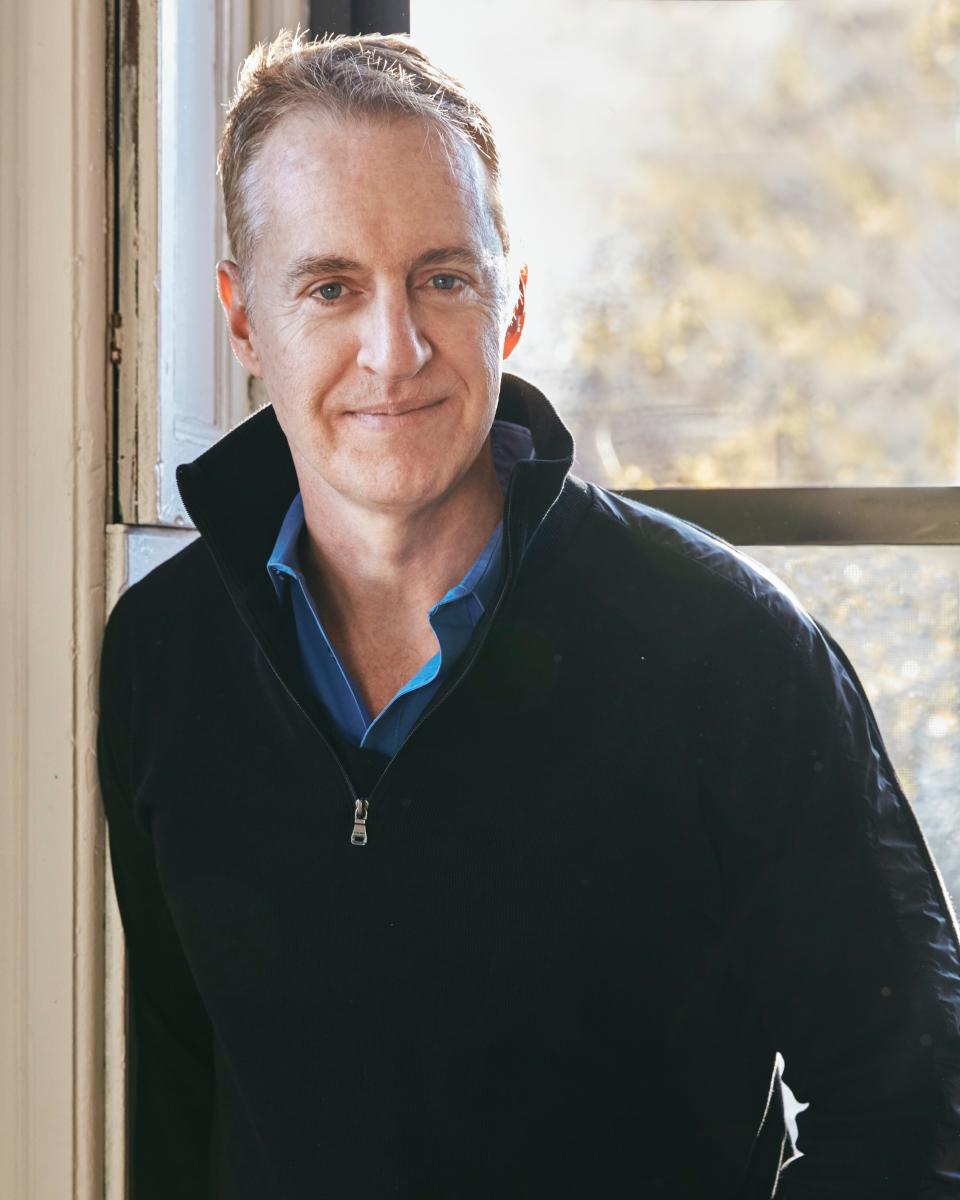

Dave Cullen had just sat down to lunch – a Budget Gourmet frozen meal of beef stroganoff – when the media first reported shots fired at a school in Littleton, Colorado, on a warm April day a quarter of a century ago.

Jaclyn Schildkraut was home sick during her freshman year of college watching soap operas – "Days of Our Lives," she thinks – when the news broke in with aerial videos of SWAT teams and terrified students running out of Columbine High School with their hands over their heads.

Robert Thompson stayed awake watching the late-night news program "Nightline," the interviews with survivors and their parents, the haunting video of then-17-year-old Patrick Ireland falling, bloodied, out the window of the school library into the arms of first responders.

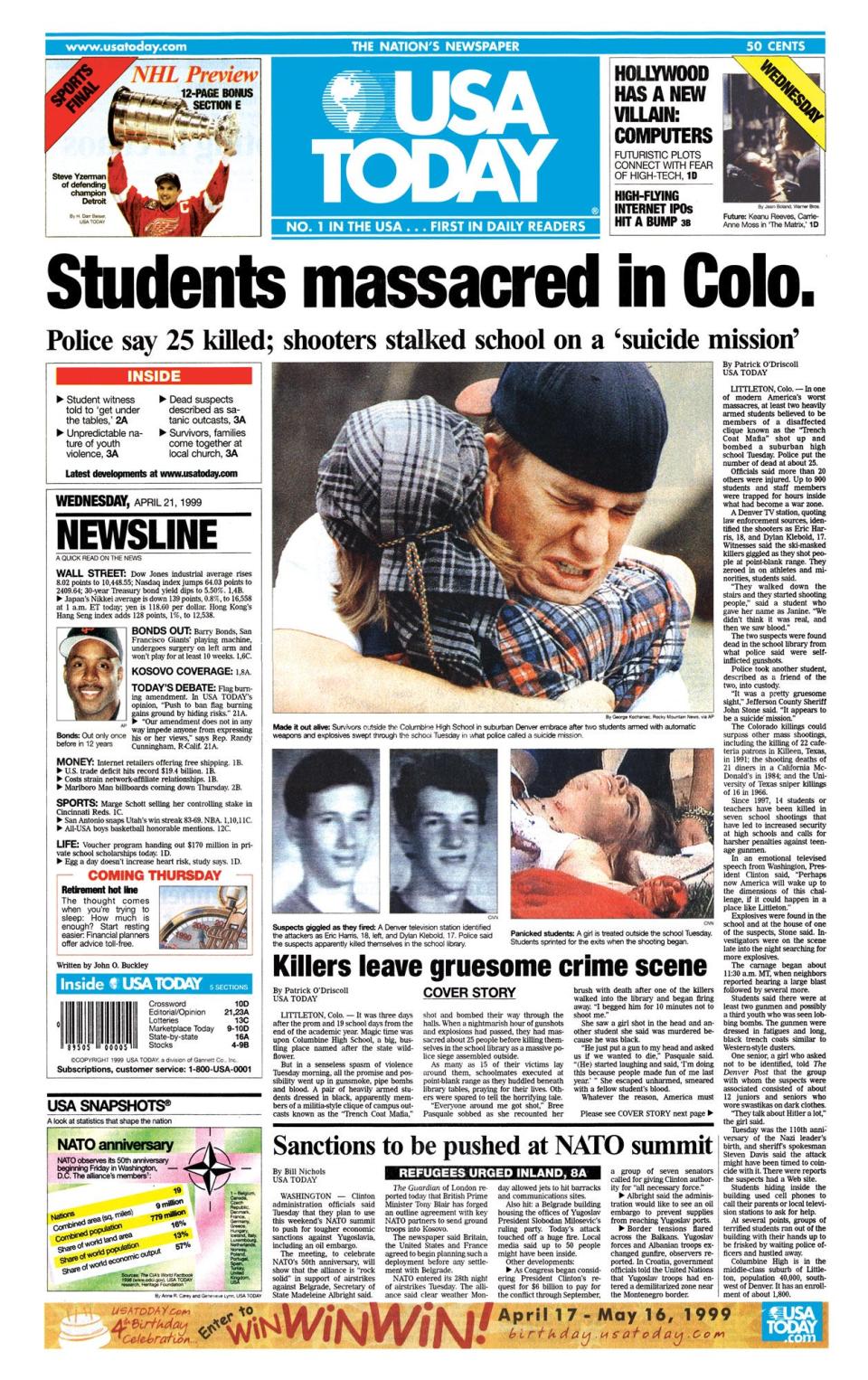

The massacre at Columbine on April 20, 1999, during which 12 students and one teacher were killed, wasn’t the United States' first mass shooting at a school, nor would it be the last. But media experts told USA TODAY it quickly became one of the most infamous thanks in part to the advent of the 24-hour news cycle and the internet. In what felt like real time, the shooting sent shock waves through the Colorado community and the nation, shattering the belief that children were safe at school.

“It was seared into us,” said Cullen, journalist and author of "Columbine." “I wasn't calling it the start of the mass-shooter era then, but we knew we were into something new and horrible.”

The trauma of Columbine still haunts the country 25 years later, including students who weren’t alive to witness it. The massacre became a blueprint for dozens of copycats, led to major changes in school safety, and sparked an enduring legacy of activism as survivors push for better gun control and offer their support to the next generation of Americans affected by gun violence.

“There's no healing," Cullen said. "It's an open wound.”

Mass shooting news can cause stress

At the time, the massacre at Columbine wasn't the nation's deadliest school shooting, said Thompson, a trustee professor of television and popular culture at Syracuse University. But the shooting came after the formation of CNN, Fox and MSNBC, which made it the first to get 24/7 television news coverage, which Thompson called “powerful and remarkably upsetting.”

Columbine was more closely watched than any other news story that year or that decade, except for the 1992 verdict in the Rodney King beating and the 1996 crash of TWA Flight 800, according to a 1999 survey from the Pew Research Center.

Shocking images were broadcast and television anchors interviewed students calling from inside the building, fueling the feeling that the disaster was still unfolding, Cullen wrote in "Columbine." Though the shooting ended just after noon, it would be several hours before police, the press and the public learned the perpetrators were dead, said Cullen, who covered the massacre for Salon. He said that may have contributed to the tragedy's staying power in the nation’s collective memory.

“We lived through it live,” he said.

Another factor was the media's focus on the shooters, who intentionally left behind a collection of evidence that later would become celebrated on "some of the darkest corners of the internet," according to James Densley, professor of criminal justice at Metropolitan State University in Minnesota.

“It was a mass shooting designed to go viral before we knew what going viral even meant,” Densely said.

Research on mass tragedies in the decades since has found the more time people spend watching this kind of news, the more likely they are to report high levels of acute stress, according to E. Alison Holman, a professor in the school of nursing and department of psychological science at the University of California, Irvine. This is particularly true when the images are graphic, Holman said.

In a study on the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, Holman found consuming six or more hours a day of media coverage about the attack was associated with more acute stress symptoms than actually being at the site of the bombing. She said symptoms can include intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, shallow breathing and increased heart rate. The effects can last for years, Holman said.

Columbine anniversary can be difficult for survivors

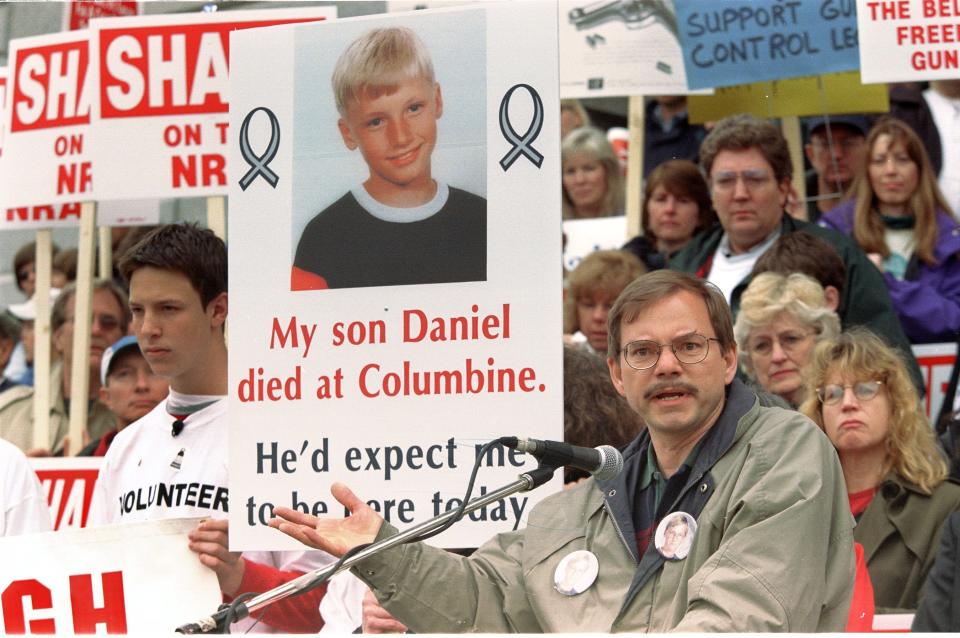

It’s trauma that Tom Mauser, whose son Daniel was killed at Columbine, believes people still don’t understand. Mauser said the anniversary of the shooting can be a particularly tough time. He said he helped plan a vigil for the victims Friday evening on the steps of Colorado's Capitol, but for survivors its a day "you want to get past quickly."

“It goes beyond just the ones who were killed or injured,” Mauser said. “The trauma can be quite crippling for some people.”

In the years since the shooting, Mauser has fought for stricter gun legislation as a member of Colorado Ceasefire. When speaking publicly, he wears the shoes his son was wearing the day of the massacre.

After Columbine, many survivors of mass shootings have followed in Mauser’s footsteps, including survivors of the 2018 attack on Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Though activism can lead to burnout, research on climate change anxiety published in Current Psychology and sexual assault trauma published in the Journal of Counseling Psychology suggests engaging in activism can benefit participants' mental health.

In 1999, sustained mental health services were "not a thing,” said Missy Mendo, who was a 14-year-old freshman at Columbine at the time. The county provided six weeks of free mental health care, which Mendo said she used, but she did not return to therapy until years later, after she became a mother.

Mendo is director of community outreach for The Rebels Project, an organization formed by a group of Columbine survivors after the 2012 mass shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. The organization offers peer support to survivors of mass casualty events.

Though it's not a substitute for traditional counseling, Schildkraut, author of "Columbine, 20 Years Later and Beyond: Lessons from Tragedy," said her research has found connecting with a "survivor network" can be a crucial part of recovery.

Each year around this time, Mendo tries to plan something to take her mind off the memories. But she knows she can’t escape the calendar, and her "brain has the potential to turn to mashed potato,” she said with a laugh.

Copycat school shootings after Columbine

Columbine also spawned something more insidious: copycats. A study of 46 active shooter incidents at K-12 schools found nearly half of the shooters were influenced by Columbine, including the attackers in Parkland and Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, according to Densley, the Metropolitan State University professor who was a co-author for the study. A Mother Jones investigation in 2019 documented the "Columbine effect" in 74 plots and attacks spanning 30 states.

“These are events where the search histories of the shooters were that they were searching for Columbine, that they were engaged in chat rooms online where they were discussing Columbine or learning about the shooters,” said Densley, co-founder of the Violence Prevention Project. “There's examples as well of shooters who have dressed in black trenchcoats because that is part of the performance of violence that Columbine created.”

Though mass shootings are rare, 75% of people ages 15 to 21 said they are significant sources of stress, according to a 2018 survey by The Harris Poll for the American Psychological Association.

Columbine itself continues to be a target, too, said John McDonald, former executive director of school safety for Jefferson County Schools in Colorado. McDonald said security at Columbine costs more than twice that of any other high school in the district.

“Columbine was unique because when I started we still had tour buses showing up trying to drop people off to take tours of the building, and it was insane,” he said. “But we also had threats because of a fascination. A fascination and fixation on the tragedy and the killers.”

McDonald said that in his 14 years on the job, the threats never waned, and ultimately they reached a crescendo around the 20th anniversary of the massacre. In April 2019, a Florida teenager authorities described as “infatuated” with the shooting flew to Colorado and bought a shotgun in Littleton, prompting school shutdowns. The teenager was later found dead of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound.

"It was an incredibly scary time," McDonald said.

Adam Lankford, a University of Alabama criminology professor who has researched mass shooters, said the media attention on the perpetrators at Columbine may have contributed to this “contagion effect." Movements like No Notoriety, a campaign created by parents of Aurora theater shooting victim Alex Teves, now urge the media not to publish mass killers' names and photos.

But Lankford warned that media attention is not the only factor driving copycats.

“It doesn't mean there's a simple effect where it's like you learn about Columbine and that makes you want to kill people,” Lankford said. “It's more complicated than that. These people have other problems in their lives, other issues in terms of their psychological health.”

Shooter drills can cause anxiety

Sometimes, McDonald said, he feels "incredibly hopeful" about the progress in school safety since Columbine. Other times he's frustrated to see schools failing to take simple precautions like locking doors. He doesn’t want to be having these same conversations 25 years from now.

“We'd better be willing to get great, because those school shooters are studying. They're studying the past. They're studying the tactics. They're studying strategies. They're studying the training,” McDonald said. “They're preparing for us − we'd better be prepared for them.”

Protecting schools and being vigilant is vital, but it takes a toll, he said. More than a year ago, McDonald decided he needed a change and left Colorado.

“What I can tell you is that after all the years I did that work, I was flat worn out,” said McDonald, now chief operating officer of Missouri’s Center for Education Safety and the Council for School Safety Leadership. “I felt like this is a 24-hour-a-day way to live. And it was exhausting, it was emotional, it was physically taxing.”

School security, which has become a multibillion-dollar-a-year industry, can be taxing for others, too. Research by the Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund and the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Social Dynamics and Wellbeing Lab suggests an association between active shooter drills and increases in depression, stress and anxiety among students, parents and teachers.

Cullen, the author, said that like the changes in airport security after 9/11, new security measures at schools after Columbine can be for some a reminder of the tragedy.

"America changed overnight in our fears and our behavior because of this," Cullen said. "Not only has no other shooting done that, but very few events, period."

Contributing: Reuters

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Columbine High School shooting still impacts us 25 years later